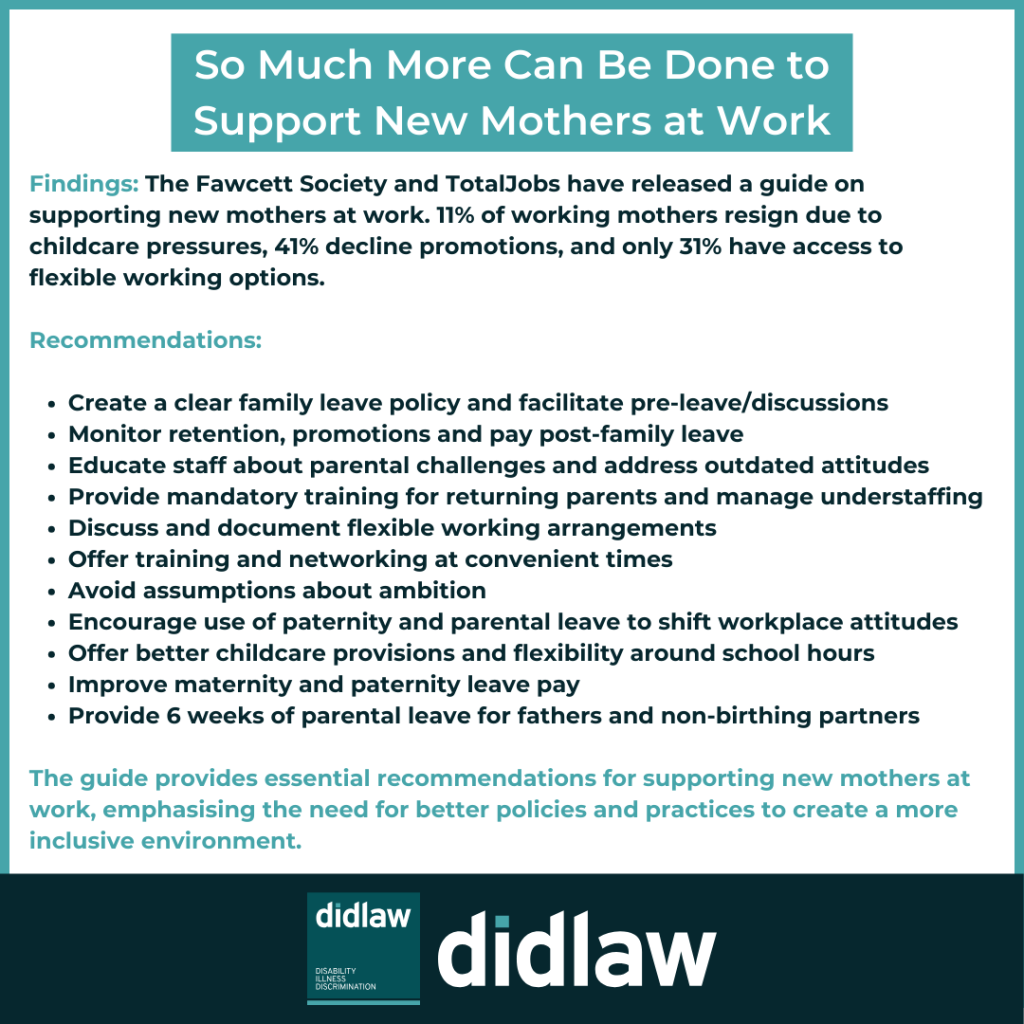

The Fawcett Society, in collaboration with TotalJobs, has published an employer’s guide on supporting new mothers at work, which is part of the same series as its guide on fertility at work.

Key findings include that, due to childcare pressures:

- 11% of working mothers resign

- 41% decline a promotion

- only 31% have access to flexible working.

The Fawcett Society’s recommendations for employers include (with didlaw comments in italics):

- Build a clear policy framework. This should be shared with management and employees to facilitate productive conversations before family leave begins. Such conversations should include agreeing contact while on leave, scheduling keeping-in-touch (KIT) days, booking a return to work meeting, providing guidance on flexible working and highlighting support available.

There’s nothing new here, it’s just that many employers still fall short.

- Use data. This enables employers to track retention, training, promotion and pay of employees after family leave and set targets for improvement.

If employers tracked the cost implications of the new mother attrition rate this might spark some interest in keeping new mothers in the workplace.

- Foster a positive and inclusive culture. Educate staff to build a culture that understands the challenges faced by parents, values their contributions and avoids assumptions.

Again, this is nothing new but cultural change appears to be the hardest to make and old-fashioned attitudes remain quite entrenched.

- Upskill managers. Consider compulsory management training focused on supporting returning parents and log management discussions with staff so that consistency of support can be monitored.

Another issue here that cannot be overlooked is the extent to which managers are left understaffed when people take time off for family. Are employers making adequate provision for cover to tackle the resentment that can creep in among managers and other workers who are in the workplace left to pick up the work of the leave taker?

- Embed flexible work options. Have open conversations with returning parents to find working patterns suitable for both parties, communicate any core requirements and document what is agreed. Consider short-term flexible working while a returning parent transitions back into work. Avoid using “business needs” to reject flexible working requests, instead provide evidence and explore alternative arrangements when requests are challenging to accommodate.

This is an area where dialogue could achieve so much where process falls short. But the parties to any discussion must have the confidence to be able to have such discussions. Perhaps another form of protected conversation is possible around this where the parties can talk freely and find solutions without the fear of reprisals or legal issues.

- Foster development opportunities. Make no assumptions about the ambitions of new parents, schedule training and networking events during core business hours and build time for part-time staff to take part.

Assuming that a new mother will have her eye on something other than work and removing development opportunities is an ongoing source of strife. Certainly for a first child where there is a major lifestyle change a period of adjustment may be needed but don’t write off staff who just need to catch their breath and adopt a new routine before they are given the chance. Judging too early is a sure way to lose great talent.

- Support paternity and parental leave. Promote, educate and encourage uptake of paternity and parental leave.

We’ve all said it: until men take leave on par with women will the workplace really change it’s attitudes to maternity leave?

- Champion affordable childcare. Advocate for changes to childcare provision from the government. Educate management about the pressure brought by childcare and how it can be alleviated, such as scheduling meetings within school hours or being flexible about the days employees are required in the office.

I don’t know what the solution is here to affordable childcare but this is a key reason women in particular do not return to work. The Government can and should intervene with financial assistance. In the meantime employers can do so much more: we routinely see new mothers facing meetings in the evenings that are always going to be difficult. An ounce of consideration costs nothing. A new mother has enough hurdles to pass without having to justify why she cannot work late – and anyway, why should she?

The report also calls on the Government to require employers to advertise the flexible work options available to applicants, pay maternity and paternity leave at an affordable rate, and provide at least six weeks of parental leave exclusively for fathers and non-birthing partners.

It’s all good advice. Now we just need more employers to pay attention to it.

You can read the full report here. Paths to parenthood: Uplifting new mothers at work.

This blog was written by Karen Jackson, MD of didlaw and a fierce advocate for working mums.