Drivers Fired by Racist Software

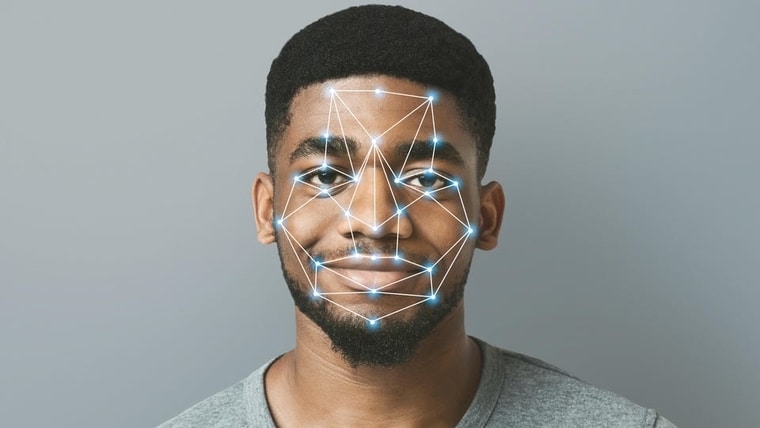

Uber may be in hot legal water again. Two unions are backing legal action against the platform in the Employment Tribunal, alleging that the use of facial recognition software constituted indirect race discrimination against their members.

The Independent Workers Union of Great Britain (IWGB) and App Drivers and Couriers Union (ADCU) state that Uber’s policy of requiring drivers to log-in by verifying their identity using a facial recognition software is discriminatory due to the higher percentage of inaccurate results when used by black and minority ethnic workers. Failed verification can lead to driver accounts being locked or deactivated.

The Equality and Human Rights Commission is also supporting the case being pursued by the ADCU.

In their report on the claim, the IWGB highlights a 2018 study on similar software to that used by Uber, which found a failure rate of 20.8% for darker-skinned female face and 6% for darker-skinned male faces. The union contends that this is especially significant given the fact that 95% of Uber’s London workforce are people of colour.

The issue is further compounded by the fact that Microsoft, the manufacturers of Uber’s facial recognition software, has previously conceded that the technology did not work as well for people of colour and could fail to recognise them.

For a claim for indirect discrimination to succeed, the Employment Tribunal will need to be satisfied that the employer operates a policy, criterion, or practice that whilst neutral on its face, has the effect of disadvantaging a group of people with a particular protected characteristic.

Judging against just the preliminary facts, this appears to be the case: supposedly neutral facial recognition software is disadvantaging a group of people sharing the protected characteristic of race. Perhaps Uber’s best method of defending the claim would be to argue that the PCP is objectively justified: that facial recognition software is a proportionate means of achieving the legitimate aim of driver and rider security. What, after all, would the alternative be?

The unions states that a less intrusive method should have been used, but what would this encompass: security questions for drivers? Biometrics? Live video verification? The availability of a better, non-discriminatory alternative is sure to be one of the main arguments on which the case revolves. Whatever the arguments, the burden will be on Uber to prove the reasonableness of their policy.

As a final point, it is an interesting note that a year ago, this claim would not have been available to Uber drivers. It is only since the Supreme Court ruling of February 2021 that found that Uber drivers should be classified as workers rather than self-employed contractors.

This means that the drivers are now eligible to bring a discrimination claim against their employer under the Equality Act 2010. Whether these claims succeed or not, the fact that it has been able to be brought at all demonstrates the importance of worker status – and why the fight needs to continue against the precarious employment practices of the gig economy.

This article was written by Michael Green – Paralegal at didlaw