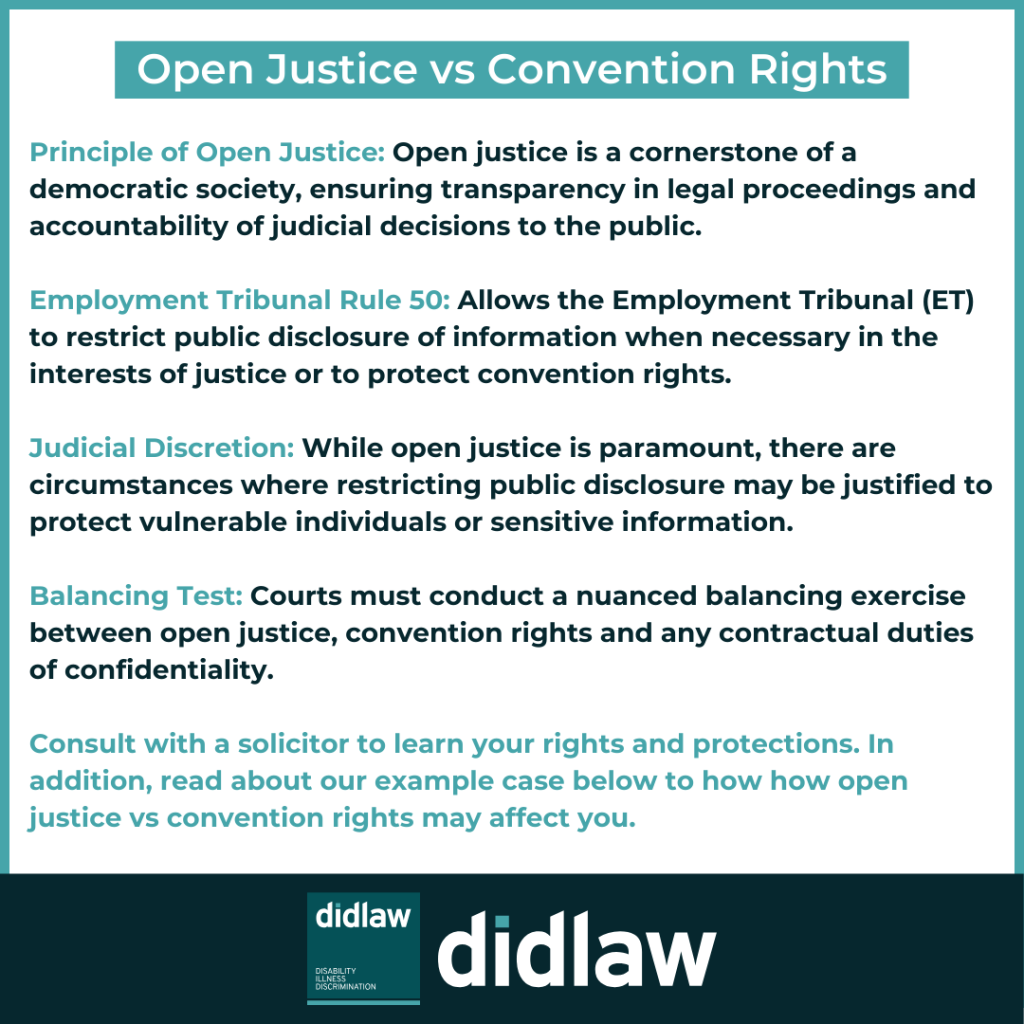

A case of open justice vs convention rights has recently been put under the microscope. Open justice is an essential tenet of a democratic society. There are, however, limited circumstances in which the principle of open justice can be trumped in favour of something more important.

Rule 50 in the Employment Tribunal (ET) allows the ET to derogate from the principle of open justice by making an order restricting the public disclosure of information where necessary in the interests of justice, or in order to protect the rights of any person under the European Convention on Human Rights (Convention).

When considering making an order under this rule, the ET must give full weight to the principle of open justice. This conflict recently reared its head in the case of Clifford v Millicom Services UK Ltd.

Mr. Clifford was employed by Millicom as a global investigations manager. His role involved conducting investigations into suspected wrongdoing in Millicom’s operations. Mr. Clifford was dismissed in 2019 on the grounds of redundancy. He subsequently brought claims in the ET, alleging Millicom had dismissed him because he had made protected disclosures. The protected disclosure he made to Millicom was that its staff had tracked the mobile phones of a prominent citizen of another country, then they had disclosed those tracking findings to a government agency there, and as a result that customer was a victim of a serious criminal offence. Mr. Clifford asserted he was primarily dismissed for reporting the matter.

Millicom applied to the ET for a rule 50 order which would prohibit the disclosure or reporting of the identity of the customer, details of the attack, and the alleged link between the attack, the company and its staff during the ET proceedings. They argued the order was necessary in the interests of justice, to protect various Convention rights, namely: Article 3 (prohibition of torture), Article 5 (right to liberty and security), Article 6 (right to a fair trial) and Article 8 (right to respect for private and family life).

Millicom said that if the information was made public, the safety and security of current and former Millicom staff would be put at serious risk. They also argued that Mr Clifford owed Millicom a contractual duty of confidence, a breach of which would not be justified in the public interest.

The ET dismissed Millicom’s application on the grounds that it could not protect the Convention rights of individuals outside the jurisdiction of the signatory States and that although Clifford owed a contractual duty of confidence, this could not outweigh the principle of open justice.

Millicom appealed this decision, and the Employment Appeal Tribunal (EAT), who found in their favour, directed the matter be remitted to a freshly constituted ET. The EAT concluded that the ET had erred by:

Not considering whether the evidence justified an order in the interests of justice at common law;

Failing to consider whether the evidence justified an order under Articles 6 and 8;

Failing to conduct a proper fact-specific balancing exercise;

Failing to address the question of whether it was in the public interest for the contractual duty of confidence to be breached by disclosure in the proceedings.

Mr Clifford then appealed to the Court of Appeal who ultimately dismissed Mr Clifford’s appeal.

This serves as a reminder that open justice is not an inalienable right and there are certain circumstances, such as convention rights, where serious consideration must be given as to whether justice should be conducted in a controlled environment that balances the rights of all those involved.

This blog was written by Jack Dooley, Trainee Solicitor at didlaw.