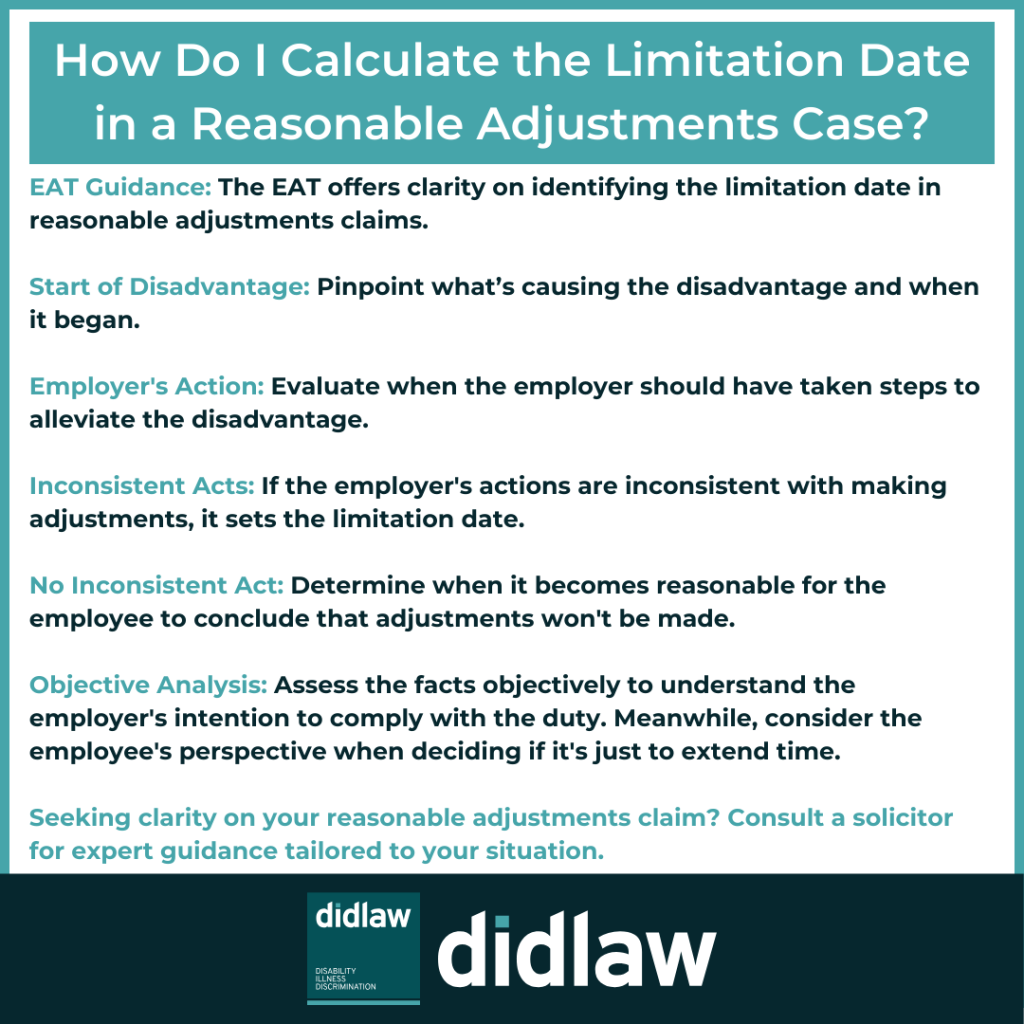

The EAT has provided welcome guidance on the identification of the relevant limitation date in a reasonable adjustments claim. Where there is no finding that the employer has made a specific decision not to alleviate a disadvantage it is down to judicial analysis to then identify the relevant date. The first step is to identify the relevant feature which causes the disadvantage which then dates the start of such disadvantage. Then follows a fact-finding exercise to ascertain when it would have been reasonable for the employer to have taken steps to alleviate the disadvantage. This then ‘dates’ when the breach of the duty to make reasonable adjustments occurred.

If there are facts that allow the Tribunal to determine that the employer acted inconsistently with its duty to make reasonable adjustments then this determines the ‘notional’ date for the purposes of limitation. If there is no inconsistent act by the employer then there will come a point when it would be reasonable for the employee to conclude that the employer is not going to make the reasonable adjustments, in breach of the duty. In such circumstances the identification of the notional date becomes a jurisdictional question in which there should be an objective analysis of the facts as known to the employee. The basis for this is what would a reasonable person conclude from those facts about the employer’s intention to comply with the duty.

At this point the Tribunal can consider the employee’s subjective frame of mind when considering if it is just and equitable to extend time. In this case, Fernandes v Department for Work and Pensions [2023] EAT 114, the Judge was entitled to consider the extinction of a duty to make an adjustment in objectively finding that a reasonable employee would not expect the duty to be complied with from a date which related to the discharge of the duty. The Judge also had not considered when a reasonable employee would have considered that to be and had also not considered whether the potential discharge was simply a temporary position. The Employment Tribunal had got it wrong at first instance.

This blog was written by Elizabeth McGlone, Partner at didlaw