Sometimes, you read a case so sad that you must write about it. This is one such case.

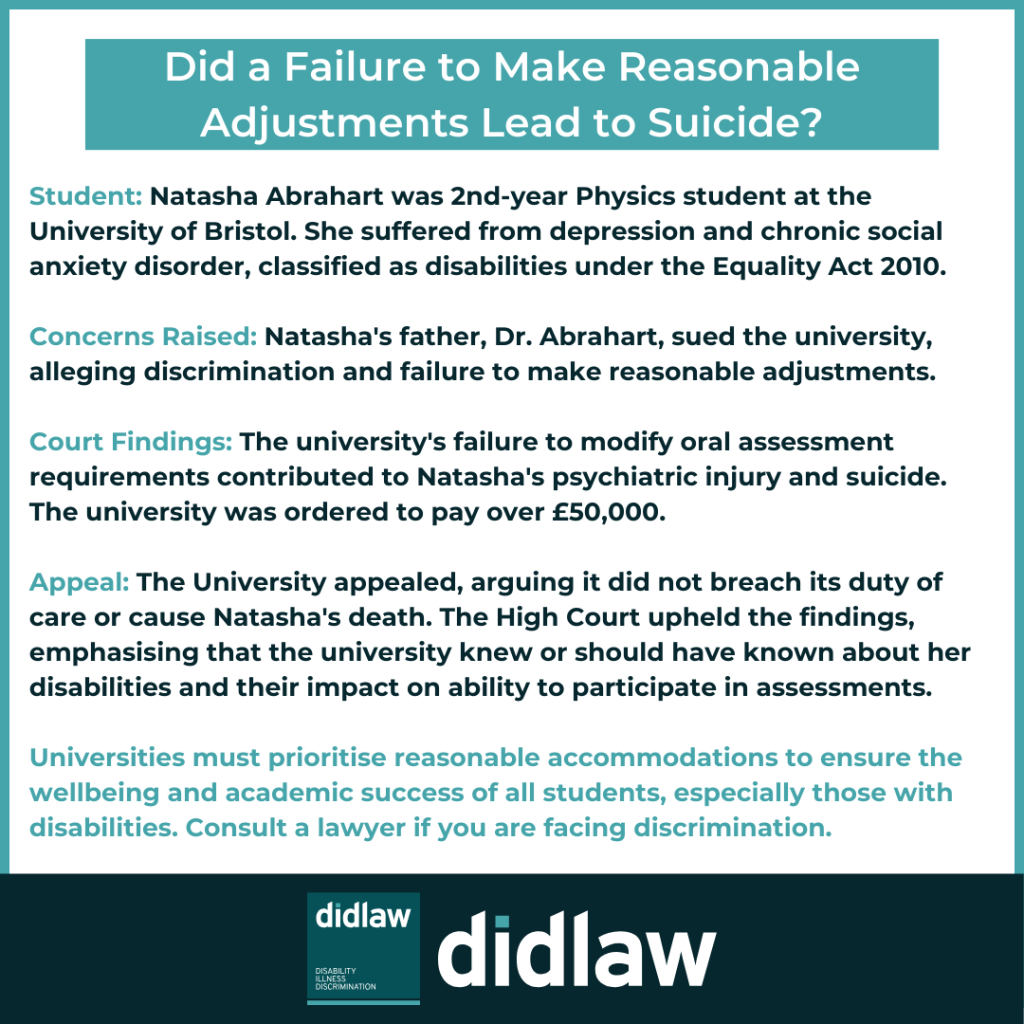

Natasha Abrahart tragically took her own life on 30 April 2018. She was a second-year Physics student at the University of Bristol. She suffered from depression and chronic social anxiety disorder. She was disabled under the Equality Act 2010, i.e., she suffered from a mental health impairment that was long term and had a substantial impact on her ability to carry out normal day to day activities. Her disabilities substantially impaired her ability to participate in oral assessments and in particular, interviews and a laboratory conference about experiments she was required to carry out as part of a mandatory module called “Practical Physics 203”. On the day of her death, she had been due to deliver a presentation in front of more than 40 students in a 329-seat lecture theatre.

Natasha’s father, Dr Abrahart brought a claim against the University on behalf of her estate that Natasha had unlawfully suffered discrimination arising from her disability, that she had been indirectly discriminated against because of her disability and that the University had failed to make reasonable adjustments. He also alleged that the University had been negligent.

At the core of this case, he argued that the University should have removed or adjusted the oral assessment requirements of Natasha’s course, so that she did not have to participate in them, and that she should not be marked down or penalised if she did not complete these assessments. The County Court determined that the failure to do this, and other deficiencies in relation to their handling of Natasha’s situation contributed to her suffering psychiatric injury and to her suicide. The Court ordered the University to pay more than £50,000 in damages, which included the costs of Natasha’s funeral.

The University appealed all the County Court’s findings in relation to breaches of the Equality Act and reasserted that they had not breached their duty of care to Natasha on grounds that the County Court was wrong to find that it knew or ought to have known enough about Natasha’s conditions to adjust the assessments. They further alleged that the University had acted reasonably “given the importance of maintaining academic standards, and fairness to other students”. It also argued that even if the County Court concluded that there had been a breach of the duty of care owed to Natasha, it did not cause her death.

The High Court rejected the University’s appeal. Mr Justice Linden held that the University knew or ought to have known that Natasha was suffering from a disability that had a substantial impact on her ability to do oral assessments by February 2018, some two months before she died. The judge said that “what a disabled person says and/or does is evidence.

There may be circumstances, such as urgency and/or the severity of their condition, in which a court will be prepared to conclude that it is sufficient evidence for an educational institution to be required to take action”. The High Court upheld the County Court’s decision that the University had failed to modify its requirements that Natasha participate in oral assessments due to her disability and that this contributed to her death.

The judge refused to make a finding that the University owed Natasha a duty of care in negligence. He declined to do so, stating that the “issue is one of potentially wide application and significance.” Natasha’s parents have called for there to be a statutory duty requiring universities to act with reasonable care and skill to avoid harming students.

I do not believe that there is any Government appetite to introduce such a duty into law because it could instigate a flood of potential claims against already financially strapped educational institutions. What this case does make clear is that an educational institution must be proactive in dealing with disabled students to ensure that they can effectively complete their studies without suffering substantial disadvantages, the consequences of which can be devastating.

The judgment can be found here.

This blog was written by Anita Vadgama, Partner for didlaw.