New year, new job anyone? Beware of discrimination in recruitment!

January is always an active month in recruitment. Combine the review of business needs with career themed new year’s resolutions and it’s no wonder there is such a flurry of activity at recruitment agencies and on Linkedin this month.

The good news for workers is that it’s an employee’s market out there at the moment with many businesses concerned about resource shortages and talent retention. Recent didlaw blogs have focused on the buoyant jobs market and the great resignation.

But recruitment is not always plain sailing for the job seeker or employer as issues and concerns frequently arise regarding the fairness and transparency of the process. Some individuals face additional challenges, both in terms of the recruitment process itself and with the lack of job offers. One recent didlaw blog, focusing on age discrimination highlighted a report finding that 50% of those over 50 believed that age had negatively impacted on employment prospects. We all are familiar with similar stories for pregnant women, new parents and obstacles related to race in the workplace and the disability employment gap.

It is unlawful for employers to discriminate against job applicants in relation to a protected characteristic. Under the Equality Act 2010 these currently include:

- Age

- Disability

- Gender reassignment

- Marriage and civil partnership

- Pregnancy and maternity

- Race

- Religion or belief

- Sex

- Sexual orientation

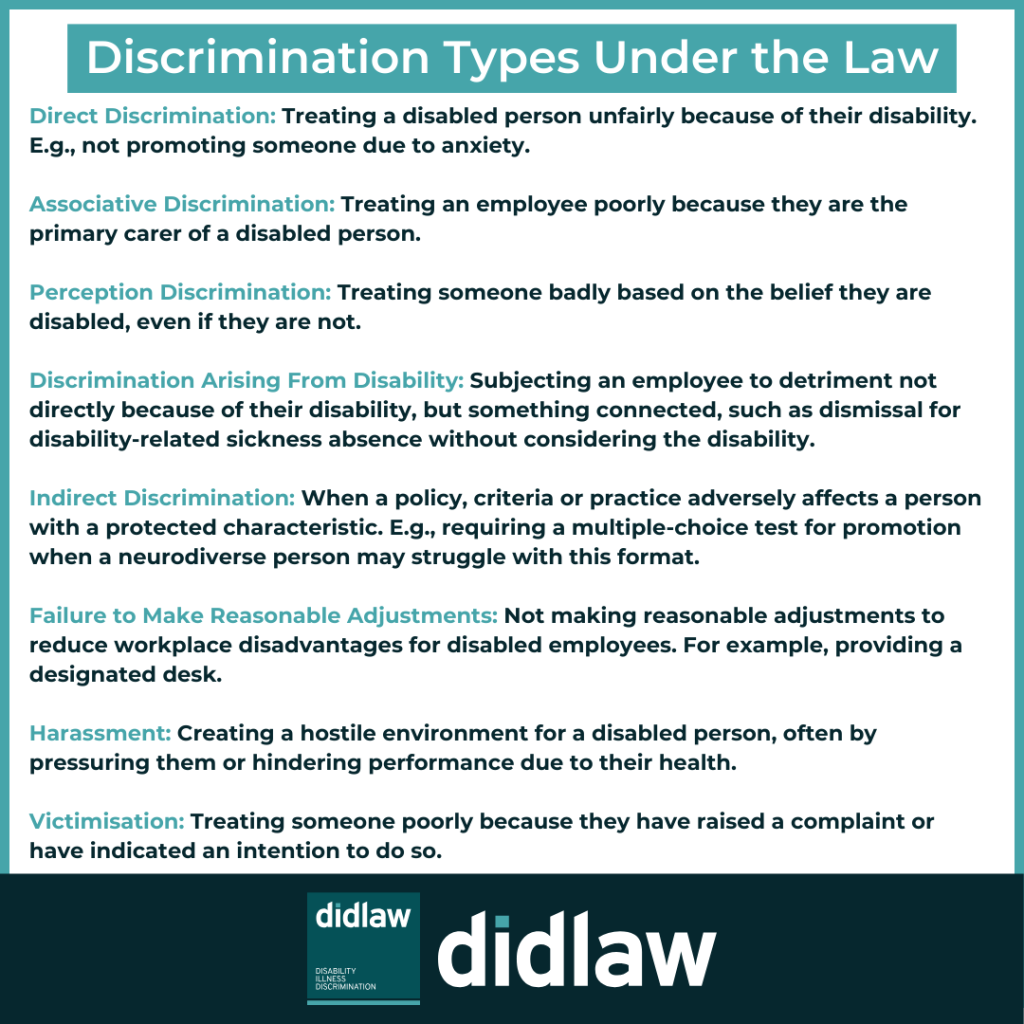

Discrimination in recruitment can occur in a number of ways – some are obvious, some less so.

The clearest form, direct discrimination, occurs in recruitment when someone isn’t selected (for interview or employment) or disadvantaged in the process because of a protected characteristic.

However, hiring discrimination can occur when there is less of a direct or obvious link. For example, if the candidate is treated less favourably because or something arising in consequence of their disability, this can also give rise to a claim, unless it can be objectively justified. By way of example, if a dyslexic candidate was not selected following a written test which produced a number of typos when writing was not a key feature of the role. This less favourable treatment may be because of something related to their disability, rather than because of it. Each claim would turn on its own facts, as always. Also, in many of these cases the job seeker would only have a claim if the employer had knowledge of the disability, which they may not as it is generally unlawful to ask for health related details.

Similarly, if certain criteria or conditions are applied in the recruitment process or with the selection criteria which disadvantage a certain group this can also give rise to indirect discrimination. So, on the face of it, there may be rules or arrangements that apply equally to all, but which, in practice, could be less fair for a candidate because of their protected characteristic. For example, the insistence that a new role is full time indirectly discriminates against women. Because the majority of part-time workers are women, if part-time workers are excluded from an opportunity or disadvantage in another way, this could give rise to an indirect discrimination claim. Similarly, advertising for a ‘recent graduate’ or ‘highly experienced’ worker could indirectly discriminate on the grounds of age.

A further potential indirect discrimination in recruitment scenario may arise if an employer will only offer a job to those vaccinated against Covid. The no jab, no job topic has been covered in previous didlaw blogs, including this one by Karen Jackson. It’s a new, evolving and intriguing area of law currently being tested in the employment tribunal.

There is also an obligation to consider and make reasonable adjustments within the recruitment process in relation to applicants with a disability. Examples will include wheelchair access for the interview, a companion to provide support within the interview, additional time to complete a written test or special equipment.

Employers must also tread carefully in terms of discriminating based on criminal convictions or trade union membership.

Consideration should also be given to advertising the vacancy so that the forum, access or wording in the ad is not discriminatory. Advertising for a ‘barmaid’ or ‘handyman’ would clearly be unlawful but also issuing the vacancy listing in a men’s only magazine could lead the employer to being dragged to the employment tribunal to defend their actions. A further recent didlaw blog focused on how gendered language used in job adverts can impact the number of applicants from certain groups. We have also previously witnessed how Facebook were referred to the Equality and Human Rights Commission in relation to alleged discriminatory algorithms used to promote job adverts with one example citing that 95% of mechanic jobs were promoted to users who were 96% male.

It is also unlawful to request information during the application process that may discriminate, such as questions about marital status, children or in reference to an applicant’s health or disability. Even asking for an applicant’s age or date of birth prior to offering a job can be unlawful.

There are some exceptions to the rules. Asking about health or disability is permitted in limited circumstances, for example where there is a necessary requirement for the job that cannot be met with reasonable adjustments.

Positive action is also permitted where it can be demonstrated that the aim is to address the under-representation of a group in the workforce, profession or industry where that group suffers disadvantage connected to their protected characteristic. In these scenarios, an employer can select a candidate who possesses a certain protected characteristic over one who does not.

A further justification relates to situations where a particular protected characteristic is an occupational requirement for the role. So, when the nature of the job provides justification for choosing one person over another based on a protected characteristic when it is necessary, not just desirable, this is permitted. For example there would be a necessity for a female in a refuge for female victims of domestic violence, a religious requirement for a Catholic church seeking a new priest or in the selection for an actor to play the role of Othello in a Shakespeare tragedy.

The headline advice for employers is to ensure they have a recruitment policy in place and that those overseeing recruitment receive appropriate training to ensure fairness and transparency in the process. Diversity and monitoring forms are a good idea, although those with decision making on the firing process should not have access to the information and names or other details that identify the person should not be included.

For further information and guidance on recruitment and job applications, check out the ACAS guidance.

This blog is by Caroline Oliver, Senior Solicitor, didlaw.